Plan your visit

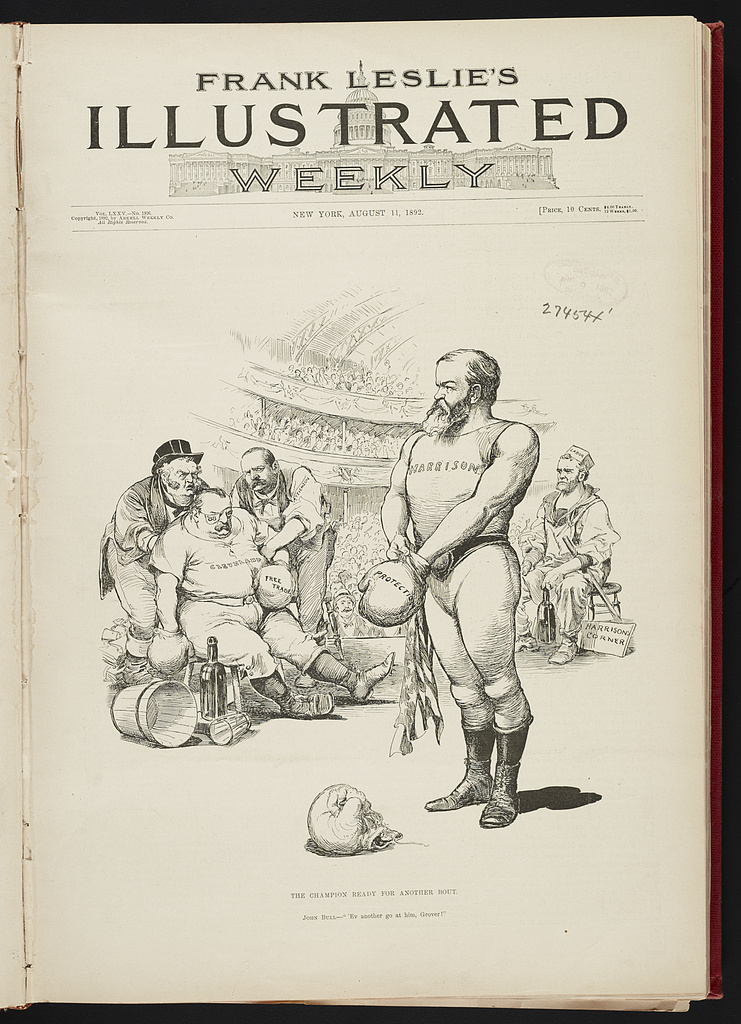

To Stand and Fight – Benjamin Harrison and the 1892 Election

February 14, 2022

As delegates to the Republican national convention gathered in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in June 1892, their choice of a presidential candidate seemed easy — incumbent Benjamin Harrison. There were, however, GOP members who still desired to have James G. Blaine, Harrison’s secretary of state, lead the party to victory in November. Other possible contenders for the nomination included Ohio governor and former congressman William McKinley, and Harrison’s longtime foe Walter Gresham.

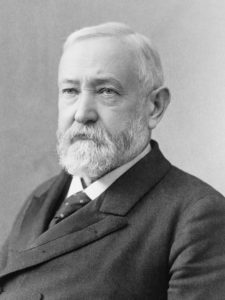

For his part, Harrison seemed unsure about whether to seek another four-year term, writing a friend, “I have not been in any state of eagerness about a re-nomination. The fact is I almost shrink from the labor and worry that is involved in a campaign.” He particularly seemed to have no stomach for a prolonged fight, noting that if his renomination, “had to be schemed for by me it was, first, pretty clear evidence that it ought not come to me: and, secondly rather a discouraging prospect of success.”

As anti-Harrison forces began to gather steam, the president became determined to run again, believing he had only two choices — “become a candidate or ‘forever wear the name of a political coward.’” He told a supporter that nobody in his family had ever “retreated in the presence of a foe without giving battle, and so I have determined to stand and fight.” On June 4, a few days before the opening of the Republican convention, Blaine submitted his resignation as secretary of state, a move that even one of his friends labeled “the most lamentable act” of his political career. Commenting to one of his aides about Blaine’s resignation, Harrison is supposed to have commented: “Well, there is one thing, I am sure to be comfortable for the next 8 or 9 months at any rate.”

Portrait of former president Benjamin Harrison, circa 1896, Library of Congress.

Blaine’s supporters aggressively pushed his candidacy at the convention, but Harrison prevailed, winning 535 1/6 delegate votes to 182 1/6 for Blaine and 182 for McKinley. Republican insider Mark Hanna, who opposed Harrison’s renomination, said that the president’s victory “seemed to fall like a wet blanket upon those in attendance upon the convention outside of the ones most interested in his nomination,” and predicted “the most lifeless campaign for a half-century.” The convention abandoned Harrison’s previous vice president, Levi Morton, for Whitelaw Reid, a newspaper owner, and diplomat. Harrison would be facing a familiar opponent, Grover Cleveland, whom the Democrats had nominated for another try at the presidency after his loss to Harrison in 1888. Both men also faced a threat from the insurgent Populist Party, which nominated former congressman James Weaver of Iowa as the candidate of its farmer-based interests.

The 1892 presidential contest paled in comparison in every way with the exciting contest four years before due the First Lady’s illness. Caroline had been unhappy with her husband’s decision to run again, asking him upon hearing the news, “Why, General? Why when it has been so hard for you.” Diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, she had vacationed for a time in the Adirondack Mountains in New York to seek some relief from her condition.

Caroline Scott Harrison, Library of Congress.

Caroline’s health, however, only worsened, and she returned to the White House in September. “Just now I am too full of anxiety about her to think of much else,” Harrison wrote a friend. Both candidates refrained from campaigning while the First Lady lay seriously ill. “I so deeply regret Father’s inability to help at this time,” wrote Harrison’s daughter Mary, “for if he was able to receive some delegations & make some speeches it would be a powerful factor in this canvas just as it was four years ago.”

In addition to his wife’s failing health, the president had to deal with serious labor unrest, with strikes by silver miners in Idaho; railroad workers in Buffalo, New York; and steelworkers in Homestead, Pennsylvania, that turned violent. Harrison had sent troops to quell the strike in Idaho, winning himself no friends among American working men. One midwestern Republican mourned how what once had been “a grand honest people’s party” had become “the slave of the money power.” For his part, Cleveland pointed to the, “tender mercy the workingman receives from those made selfish and sordid by unjust governmental favoritism.”

Caroline Scott Harrison died on October 25, and the president took his wife to Indianapolis for burial at Crown Hill Cemetery. Harrison’s grief at her death was so great that he failed to return to Indianapolis to cast a ballot for himself for president. It would not have mattered; Cleveland won solid victories in both the popular vote (5,556,918 to 5,176,108) and the Electoral College (277 to 145); Weaver captured several western states, winning 1,029,846 popular votes and twenty-two Electoral votes. In addition to winning every state in the South, Cleveland took such critical swing states as New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and even Harrison’s home state, Indiana.

Some Republicans blamed their defeat on workers, the “‘employee’ class who secretly and deceitfully votes against their employers from ‘pure cussedness.’” Business leaders also took some blame, with Henry Clay Frick, chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, coming under fire for his stubborn stand against workers in the Homestead strike. The president’s effort also suffered from lack of assistance from all party leaders, with some, a reporter related to a presidential aide, supportive to Harrison to his face, but acting like Judases when his back was turned.

Harrison felt no sting in his defeat. “Indeed after the heavy blow the death of my wife dealt me,” he said, “I do not think I could have stood the strain a re-election would have brought.” Harrison confided in a letter to Gilbert A. Pierce, U.S. Senator from North Dakota, the American people were “entitled to their will,” and if, as he believed, the programs of the Democratic Party were as wrong and destructive as he believed, the people would find out and, “as Mr. [Abraham] Lincoln said ‘wobble right.’” The outgoing president added that when he retired from public life after Cleveland took office it would be for life. Harrison wrote: “I have not enjoyed public life. Indeed it seems to me—measured by my experience and sense of time, without reference to the calendar—that I have been here [in the White House] ten years now. The time has not been broken by any period of relaxation or joyousness. The shadow of great cares have been continually over me. It is a constitutional fault of mine to carry responsibility very heavily.”

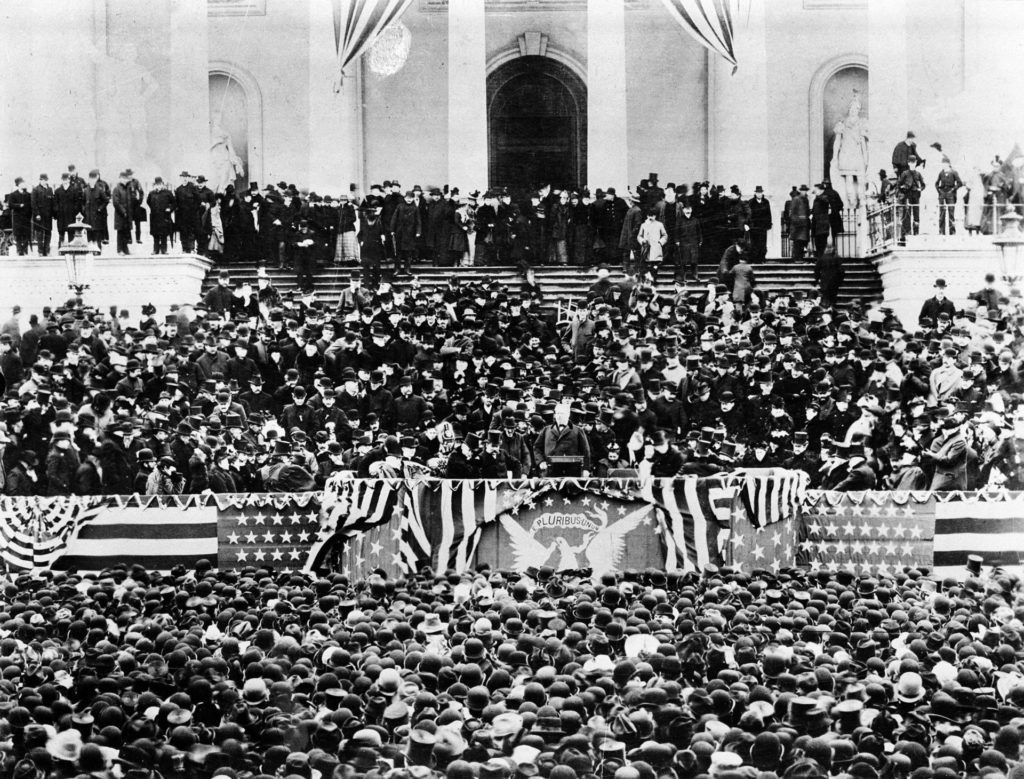

Grover Cleveland delivers his inaugural address as the twenty-fourth president of the United States on Saturday, March 4, 1893, at the East Portico of the U.S. Capitol, Library of Congress.

Harrison, the last Civil War general to serve as chief executive, accompanied Cleveland, the first man to win non-consecutive terms as president, to his inauguration on March 4, 1893. Members of his cabinet accompanied him on his way to the train station for his trip home to Indianapolis. His travel time included a stop at Richmond, Indiana, where he addressed a large crowd before a welcoming committee from Indianapolis met him in nearby Cambridge City. In Indianapolis, a cheering crowd—as large as the one that had bid him farewell four years before—welcomed his return while a band played “Home, Sweet Home.” According to Harrison, crowds jammed Illinois Street, Washington Street, and up Pennsylvania Street to the Denison Hotel. “The reception at the State House in the evening was as great a jam as I ever saw in Indpls—and the cordiality was very touching,” Harrison wrote Halford.

Reporting on Harrison’s homecoming, the Indianapolis Journal noted that no matter a person’s political party or religion, “all are proud to have Benjamin Harrison come back to Indiana to live and to be an example of what is true and noble in citizenship.” There were some things, the newspaper added, that were better than being president, especially giving the nation “the inspiration of a noble example.” Settling in once again in his North Delaware Street residence, accompanied by his daughter, Mary, and his two grandchildren, Harrison wrote his son, Russell, “I made no mistake in coming home at once — there are no friends like the old ones.”